Religious Transformation and Manipulation in Mexico

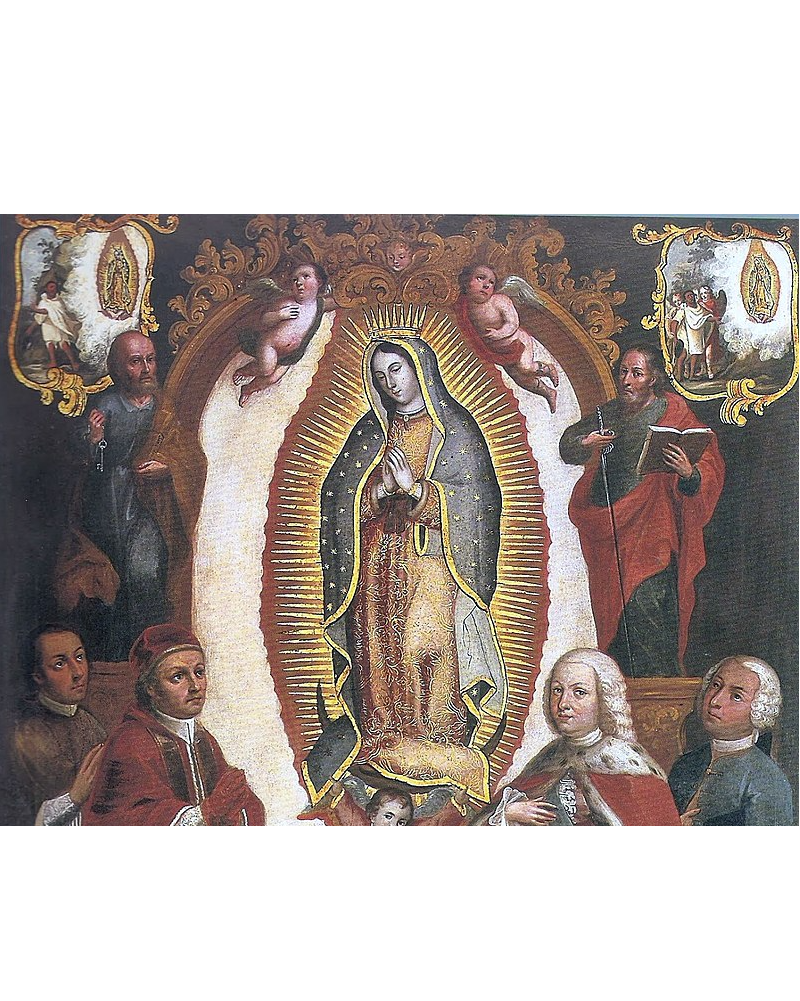

The Mexico of today displays a colorful and potent Catholic face. However, there is more to the country’s current religious identity than what the Spaniards brought with them in 1519. Throughout Latin America, religion tended to structure every single part of life, dictating festivities, sacrifice, architecture, ritual, medical practice, consumption of food, familial relations, language, and most other aspects of culture, if not all. Conversion, therefore, was a difficult task. The attachment to Mexican polytheistic religions remained, and old rituals and beliefs wormed their way into an indigenous interpretation of Catholicism.

Similarities between the figure of Quetzalcoatl and that of Jesus Christ have existed since before the process of colonization, and the points in common are used to build further connections. Although Quetzalcoatl is a feathered snake, he was thought to be born of a virgin and be able to resurrect the dead, a couple commonalities with Jesus Christ.

Another instance of similarity was the Aztec person-shaped cookie made of corn, seeds, and human blood that was eaten ritualistically in Aztecan Mexico in a way that can be related to holy communion. In addition, the Aztec headband (Hatoaní) is similar to a confirmation headband.As old symbols begun to be repurposed to serve Christianity, art related the Mayan God Maximón with either demonic entities or Saints, trying to create a comprehensive transition of faith.

With the progression of time, pastoral speech was translated into Nahuatl and other native tongues. In the search for smooth conversion, a baptism came to be translated as “precious green jade water” and Amen came to be “let there be flowers”. The creation of a wholly new culture and religious identity is a foundation of modern Mexico. All of these examples of similarities between the two create this new hybrid religion, a mix of conversion getting pushed and pre-existing faith pushing back.